The role of economic arrangements in the promotion of a free society is twofold. On the one hand, freedom in economic arrangements is in itself a component of freedom, in its broad sense. So, economic freedom is an end in itself. In the second place, economic freedom is also an indispensable means toward the achievement of political freedom. By relying primarily on voluntary co-operation and private enterprise, in both economic and other activities, we can ensure that the private sector is a check on the powers of the government and acts as a bulwark against attack on freedom of speech, of religion, and of thought.

Government can never duplicate the variety and diversity of individual action. At any moment in time, by imposing uniform standards in housing, or nutrition, or clothing, government could undoubtedly improve the level of living of many individuals; by imposing uniform standards in schooling, road construction, or sanitation, central government could undoubtedly improve the level of performance in many local areas and perhaps even on the average of all communities. But in the process, government would replace progress by stagnation, it would substitute uniform mediocrity for the variety essential for that experimentation which can bring tomorrow’s laggards above today’s mean.

There are only two ways of co-ordinating the economic activities of millions. One is central direction involving the use of coercion. The other is voluntary co-operation of individuals – the technique of the market place. The possibility of co-ordination through voluntary co-operation rests on the elementary – yet frequently denied – proposition that both parties to an economic transaction benefit from it, provided the transaction is bi-laterally voluntary and informed. Exchange can therefore bring about co-ordination without coercion. A working model of a society organized through voluntary exchange is a free private enterprise exchange economy.

The limited success of central planning (or its outright failure to achieve stated objectives) was made evident since the fall of the USSR towards the end of the 20th century. The centralised planning is inevitably in conflict with individual freedoms. The fundamental threat to freedom is power to coerce, be it in the hands of a monarch, a dictator, an oligarchy, or a momentary majority. The preservation of freedom requires the elimination of such concentration of power to the fullest possible extent and the dispersal and distribution of whatever power cannot be eliminated – a system of checks and balances. By removing the organization of economic activity from the control of political authority, the market eliminates this source of coercive power. It enables economic strength to be a check to political power rather than a reinforcement.

The government consists of the temporary executive, elected for a few years, as well as the permanent bureaucratic set up. The bureaucratic set up is inefficient, and at times incompetent and corrupt. This is the case in most countries. A bureaucracy tasked with an enterprise isn’t successful because the market place is a dynamic place. Entrepreneurs have to take risks and innovate their businesses. This is the only way they survive and grow. But individuals who are part of government bureaucracy are inept at doing this. They do not have the entrepreneurial spirit of the businessman. Bureaucrats from the government who are appointed at the head of many of the Public Sector Enterprises (PSEs) do not have a personal stake in the enterprise. If the enterprise is run badly, and incurs losses, it’s the tax payers money which is being wasted. The bureaucrat does not suffer any personal loss. If the enterprise is run successfully, the government official appointed as the head of the enterprise won’t get any great acclaim. So he doesn’t have the same stake as the private entrepreneur who runs a business and does so not only with the aim of making money, but also has the aim of creating a legacy of his own.

India is one of the biggest economies in the world. We have great prospects for the future. The thrust on equity has created a fairer society in many respects. Now that we have empowered individuals with bargaining power and better negotiating capabilities, we can move towards a private ownership model. This is the most efficient system and it creates the most number of opportunities for the best utilisation of people and resources.

As per a Confederation of Indian Industry analysis, the cumulative losses of the 55 non- strategic central PSEs (listed and unlisted) in the three years from 2016-17 to 2018-19 stood at a staggering र 45,748 crore. An exploration of the merits of privatization in the Economic Survey 2019-20 also affirmed better performance by privatized central PSEs, on an average,

than their peers in terms of their net worth, net profit, Return On Assets (ROA), Return On Equity (ROE), gross revenue, net profit margin, sales growth and gross profit per employee.

When a PSE is sold off to the private sector, the government gets the sales proceeds. Further, if the PSE had been making losses and was being subsidised, then these subsidies come to an end, which further helps the government. Thus the immediate generation of revenues is supplemented by reduction in recurrent expenditures. But does the government really gain? In the simplest case, the buyer will be willing to pay only so much as the PSE is expected to bring in the future. The PSE is expected to generate a future stream of reruns. The sum of the returns (after being discounted to reflect the fact that a rupee today is more valuable than a rupee tomorrow) is what a buyer will pay. The government would have got the same revenue had it not sold the PSE. Therefore, it would seem that privatisation does not have any real impact on the government’s finances. There are two reasons why privatisation might still make a difference. First, a privatised firm might be expected to be more efficient than a PSE. Hence, the sum of discounted returns will be higher than that under government ownership. Secondly, the government, while it privatises, is getting funds immediately. This added liquidity might be desirable for a number of reasons, for example, because the government might want to spend on education or infrastructure.

It is interesting to note that in theory, for a loss-making PSE the price might be negative. This is not very far-fetched. Governments have sometimes given so many concessions to the buyer to induce them to buy loss-making concerns, that in effect the price has turned out to be negative. Proponents of privatisation who focus on efficiency have argued that it can have an important effect on economic efficiency. Two types of efficiency gains are possible: gains in allocative efficiency, and gains in productive efficiency:

Proper allocation of the resources of the economy depends on the prices reflecting correctly relative scarcities of resources. A resource that is more scarce should have a higher price and this would lead to it being used more sparingly. In PSEs, prices sometimes does not reflect scarcities properly. For example, if the government gives a subsidy for an input used by a PSE, the PSE would tend to ‘over-use that resource. Or, if a PSE is a monopoly, then it can set its own price. Thus, if kerosene is sold at a very low price, this would encourage adulteration of diesel with kerosene (i.e., over-use of kerosene). It is evident that for PSEs operating in competitive markets, prices would better reflect scarcities and therefore allocative inefficiencywould be less. Then the gains from privatisation would also be less.

Worldwide experience shows that implementation privatisation has lagged well behind stated intentions. Barring a few countries, privatisation has been limited to small PSEs of the manufacturing and the services sector. Two kinds of obstacles to privatisation can be identified – implementation issues and political constraints.Implementation Issues Technical constraints to privatisation are related to both managerial deficiencies and weaknesses within the economy.

However, the Indian government’s pursuit of disinvestment in Public Sector Undertakings remains steadfast, poised for fresh momentum in the upcoming Interim Budget. Despite the ambitious 2023-24 target of Rs 51,000 crore, challenges have surfaced, leading to a current shortfall. However, the government aims to propel pending transactions forward, setting a new target above Rs 50,000 crore, emphasizing its commitment to disinvestment initiatives.

The recent amendment to the Income Tax rules, specifically under section 52(2)(x), marks a significant development in the government’s disinvestment strategy. The expansion of the tax exemption has far-reaching implications, aiming to streamline and expedite the disinvestment process in public sector companies.

Amendment of Income section 56(2)(x) under Income Tax Act and expansion of the scope of a tax exemption on public sector shares

The crux of the amendment lies in broadening the scope of the tax exemption previously limited to shares received by individuals from the central or state government under strategic disinvestment. The revised provision now includes “any movable property, being equity shares, of a public sector company or a company, received by a person from a public sector company or the Central Government or any State Government under strategic disinvestment.” This expansion ensures a more inclusive application of the tax exemption, covering various scenarios of equity share transactions.

The amended rule brings about a pivotal change by providing tax relief to individuals who receive shares from public sector companies below their fair market value. Under the revised provision, section 52(2)(x) exempts such transactions from tax implications. Notably, the earlier exemption was confined to share sales by the government and did not encompass fresh issues of shares by the companies themselves. This expansion is anticipated to facilitate a more seamless and comprehensive application of the tax exemption in the context of strategic disinvestment initiatives.

To comprehend the significance of the amendment, it is essential to delve into the workings of Section 56(2)(x) of the Income Tax Act. This section is pivotal in the taxation of gifts and items received without consideration or for inadequate consideration. Encompassing various assets such as money, property, shares, securities, and more, the provision becomes applicable when these assets are received for no consideration or significantly less than their fair market value. Importantly, the Income Tax Act outlines specific instances when this provision does not apply, providing clarity on its scope.

The expanded tax exemption under section 52(2)(x) is poised to play a transformative role in the government’s disinvestment strategy. By removing tax implications for individuals receiving shares below market value, the amendment aims to incentivize participation in disinvestment initiatives. This move is expected to attract more investors, promote liquidity in the market for public sector company shares, and ultimately contribute to the success of the government’s disinvestment agenda.

Key transactions in the pipeline include the strategic sale of Shipping Corporation of India and Concor, privatization of IDBI Bank, and the listing of selected PSEs. The post-General Elections period is earmarked for the execution of these plans. Notably, the Interim Budget, set to be presented on February 1, is expected to signal the government’s intent to advance these pending transactions, with the final decision on disinvestment proceeds awaiting the full Budget later in the year.

Despite revenue shortfalls, optimism persists, driven by anticipated higher dividend proceeds and robust tax collections. Recent developments, such as the search for an advisor for the Bharat Bond Exchange Traded Fund, underscore the government’s proactive stance, although challenges, such as the cancellation of the strategic disinvestment of Salem Steel Plant due to a lack of interest, persist.

Historically, meeting annual disinvestment targets has been challenging, with the BJP-led NDA government surpassing targets only twice since 2014. Recent disinvestments exceeding 51% often involved transferring stakes to other public sector enterprises, maintaining state ownership. While successful ventures like HPCL’s sale to ONGC bolstered revenue, challenges, such as the cancellation of BPCL’s stake sale, hindered progress.The current fiscal year witnessed hurdles, with the delayed LIC IPO contributing to revenue delays. Failed disinvestment attempts, like BPCL and Pawan Hans, impacted targets.

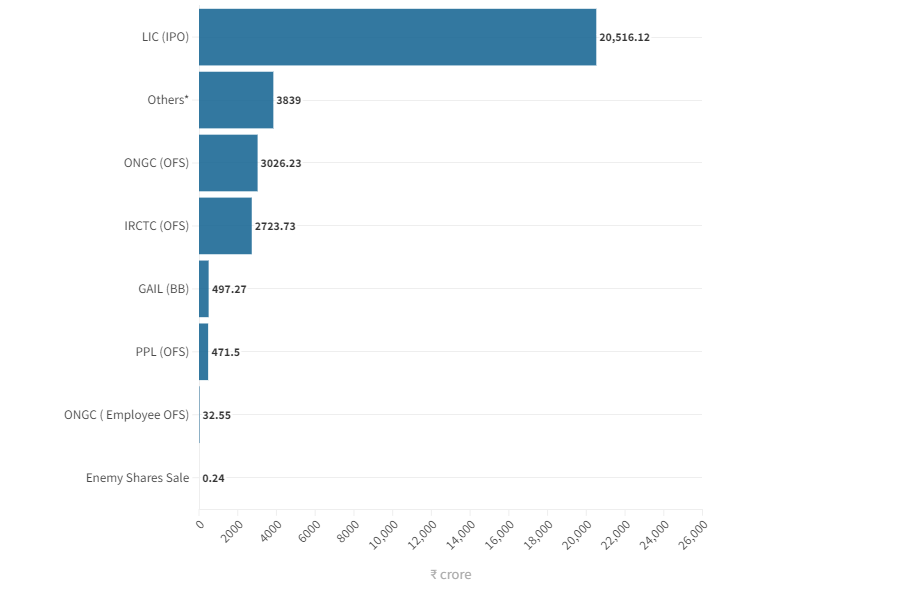

In the 2023-24 Union Budget, the government has established a disinvestment objective of ₹51,000 crore, marking a nearly 21% decrease from the budget projection for the ongoing fiscal year and a marginal increase of just ₹1,000 crore from the revised estimate. This target is also the lowest in seven years. Additionally, the Centre has not achieved the disinvestment target for 2022-23 so far, having garnered ₹31,106 crore to date. Notably, a significant portion of this amount, ₹20,516 crore or nearly one-third of the budgeted estimate, originated from the IPO of 3.5% of its shares in the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC).

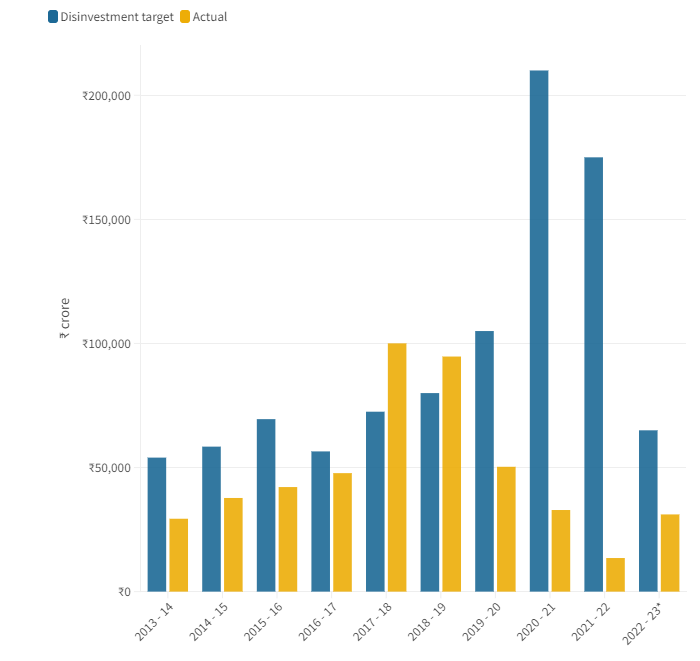

Source:Department of Investment and Public Asset Management (DIPAM), PRS legislative research •Actuals for 2022-23

Initially, over the past three decades, various central governments achieved their annual disinvestment targets only six times. Since assuming power in 2014, the BJP-led NDA government has not only met but surpassed its disinvestment goals twice. In the fiscal year 2017-18, the government garnered disinvestment receipts slightly exceeding ₹1 lakh crore, surpassing the ₹72,500 crore target. Similarly, in 2018-19, it achieved disinvestment proceeds of ₹94,700 crore, outperforming the set target of ₹80,000 crore.

It is noteworthy that PRS Legislative Research highlights a trend in recent years wherein, in instances of disinvestment involving the sale of more than 51% of the government’s shareholding in Central Public Sector Enterprises (CPSEs) along with a transfer of management control, the stake was often sold to another public sector enterprise. For instance, when the Centre exceeded its disinvestment target in 2017-18, it earned ₹36,915 crore by selling Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited (HPCL) to the state-owned Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC). Similarly, in 2018-19, REC Limited was sold to the state-owned Power Finance Corporation Limited, resulting in the government raising ₹14,500 crore.

As of February 8, 2023, the government had garnered disinvestment receipts of ₹31,106.64 crores, falling short of the budget estimate of ₹65,000 crores. No disinvestment proceeds were generated from NINL through strategic disinvestment. The category labeled ‘Others’ represents the sale of Axis Bank Shares held by SUUTI.

Source: :Department of Investment and Public Asset Management (DIPAM), PRS legislative research • IPO – Initial Public Offering; BB – Buyback; SD – strategic disinvestment; OFS – offer-for-sale

In the fiscal year 2021-22, the addition of Air India to the Tata group resulted in a significant shortfall for the Centre, missing its ambitious disinvestment target of ₹1.75 lakh crore by a substantial margin, with disinvestment proceeds amounting to just ₹13,534 crore. In the present fiscal year, a substantial portion of its budget estimate is attributed to the delayed LIC IPO, which, if not for market volatility, would have occurred in the preceding year.

The intended sale of the 52.8% stake in Bharat Petroleum (BPCL) had to be abandoned in mid-2022 due to the withdrawal of almost all bidders. Similarly, the strategic sale of Central Electronics faced a setback owing to lapses in the bidding process, and the Pawan Hans stake-sale also encountered difficulties. Despite the sale of Neelachal Ispat Nigam Ltd. (NINL) to a Tata group steel entity, no proceeds reached the Centre’s exchequer as it held no equity in the company. With disinvestment proceeds of ₹31,106 crore in the exchequer so far and less than two months left in the current fiscal year, the government is poised to fall short of its disinvestment target.

The government has decided not to include new companies in the list of CPSEs slated for divestment in 2023-24. The ambitious divestment plans, including the aspirational divestments of two public sector banks and one general insurance firm announced in the budget two years ago, will not be part of the upcoming divestment strategy. As per DIPAM, the government is steadfast in adhering to the already-announced and planned privatization of state-owned companies, such as IDBI Bank, Shipping Corporation of India (SCI), Container Corporation of India Ltd (Concor), NMDC Steel Ltd, BEML, HLL Lifecare, among others. Notably, the divestments of Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited, SCI, and ConCor, approved in 2019, are pending completion due to complications related to the physical assets being properties of the states they are located in, necessitating demerger processes. The divestment of major holdings of IDBI Bank is also in progress and is anticipated to conclude by mid-FY24.

Between FY15 and FY23 (as of 18 January 2023), disinvestment proceeds totaling approximately ₹4.07 lakh crores were realized through 154 transactions utilizing various modes and instruments. Out of this, ₹3.02 lakh crore stemmed from minority stake sales, while ₹69,412 crore resulted from strategic disinvestment transactions in 10 Central Public Sector Enterprises (CPSEs), including HPCL, REC, DCIL, HSCC, NPCC, NEEPCO, THDC, Kamrajar Port, Air India, and NINL.

The government is actively engaged in the privatization of several CPSEs, including Shipping Corporation of India, NMDC Steel Ltd, BEML, HLL Lifecare, Container Corporation of India, and Vizag Steel, alongside IDBI Bank. These strategic sale processes are at various stages of development, with the majority expected to be completed in the upcoming fiscal year commencing on April 1.

Despite challenges posed by the pandemic-induced uncertainty, geopolitical conflicts, and associated risks, the government remains resolute in its commitment to privatization and strategic disinvestment of Public Sector Enterprises. This commitment is evident in the implementation of the new Public Sector Enterprise (PSE) Policy and Asset Monetization Strategy, reflecting a determined effort to navigate the evolving landscape of disinvestment.

Some critical aspects to consider while transitioning to a pro market framework

The overstaffing in PSEs means that the restructuring process would generally involve laying off part of the workforce. Usually, forced dismissals are politically infeasible and only generate more opposition to privatisation. Governments therefore try to adopt some kind of voluntary approach. Components of voluntary approaches that, have been tried out include Monetary compensation (e.g. through voluntary retirement schemes) and Retraining/Redeployment of employees.

Sometimes the Government agrees to accepting a lower price for the enterprise in return for an assurance firm the new owner that employees will be retained even after privatisation. In the East German privatisation programme4, there is an instance where an enterprise was sold for one deutschmark, because the bidder promised to retain all the workers. Retraining can refer to giving workers training in skills that would help them to become productive members of the PSE itself. Or the aim may be to enable them to find alternative jobs in the private sector. Redeployment can be from one government PSE or Department to another, or it can be to the private sector. The process of laying off workers poses a lot of difficulties. The total cost of laying off workers can be quite high and may pose a problem to cash-strapped governments. The problem has been eased to a certain extent because multilateral agencies are now prepared to lend for severance pay packages. In many industries, salaries in the public sector are higher than in the private sector except for highly skilled employees.

Moreover, it might take a long time for a laid off worker to find an alternative employment and their earnings might be close to zero in the intervening period. Further, in most developing countries, the public sector provides health coverage as well as old age pension. The greater job security in the public sector also makes employment in this sector more attractive. If all these factors are to be taken into account, then the required compensation becomes sizeable.

It might also be argued that in developing countries, where job opportunities are so limited, one employee in the public sector might have to support a large number of unemployed members of the family. Loss of this one person’s income can affect many more individuals.5 There is also another subtle problem involved here. Once a severance package has been formulated, only the high-productivity or the superior workers may accept the package and leave, because they are certain of getting jobs elsewhere. The PSE is left with the low- productivity workers. This is called the problem of adverse selection: since the package offered is not tailored to individual needs or characteristics, any employee gets to consider the same package. But only the high-productivity workers find the package attractive and accept it.

There is a tendency to support privatization with a selective and isolated approach, and to ignore the need to introduce privatization as an integral part of economic reforms and strategy for implementation. Related to the need for policy reforms is the finding that reforms pertaining to public and corporate governance, commercial redressal, and credit recovery are, in practice, difficult to implement and enforce. These findings point to the need for programs at Early Reform Stage.

To enable better monitoring of India’s privatization/disinvestment targets, it is advisable that apart from these 31 PSEs, the government draws up a list of other PSEs in which it intends to bring down its share of ownership below 51%, or disinvest fully, in advance. This will also help to improve their valuations before the actual process of selling equity begins. The privatization of non-strategic PSEs listed on the bourses could be given priority, as they are relatively easy to offload, thanks to their publicly-known valuations.

There is also a need to improve the quality of receipts from disinvestment by going in for genuine stake sales, rather than resorting to moves that have one PSE buying another. On the lines of strict regulations in place for third-party transactions, the government should also define principles of corporate governance for PSEs, especially for those which are not listed.

The need for political commitment and the right institutional framework is of paramount importance to avoid delays and implementation constraints. Economic stabilization and trade liberalization programs are essential for success. Deregulation of the banking sector; legal reform; judicial reform; enforcement reform; public governance reforms; capital market development and restructuring to induce competition are needed for best privatization results. Significant too is the need to carry out public governance reforms before corporate governance reforms.

Its vital that unnecessary regulations be removed considering the scope for competition and its potential for unleashing innovation in business. The actions by the regulator may create major conflict, which detracts from the effectiveness of privatization. The larger regulatory authorities are typically structured with a mandate to approve prices, operating expenditure, accounts, quality of output and investments, and to monitor compliance with concessionaire agreements. Where competition has been established, small regulatory authorities consisting of no more than an appointed commissioner and secretarial staff (often covering several sectors) seem to work best. Some merit is seen in transferring the responsibility of regulators for consumer interests to a separate anticompetition trust authority. This limits the role of the regulator to monitoring and ensuring compliance with agreed operational and investment contracts. Overregulation reduces profit and the incentive to invest.

Some types of PPPs have proven difficult. They are typically structured so that the government retains ownership of the land and fixed assets. Problems that arise relate largely to overregulation and an emphasis on maintaining tariff levels without timely adjustment for variations in factor prices, force majeure circumstances, physical contingencies, and restructuring to create competition. Sometimes, PPPs are unnecessary, and a reflection of opposition to privatization. The example of privatizing, as a lease operation, the plantation estates in Sri Lanka demonstrates the lesser effectiveness of PPPs. Total privatization—as is generally the case—would have been more effective. PPPs are particularly appropriate where the capital costs of new projects are high relative to operating returns.

The tendency of governments to foist, with the sale of PSEs, welfare activities that are not core to PSE operations also enters the politics of privatization. Typical welfare attachments include hospitals, theatres, sports facilities, sponsorship programs, community residences, and schooling. If welfare services are to be provided, then the additional operation and maintenance costs should be factored in as a subsidy. The practice of privatizing without appropriate pricing, adjustment, or subsidy is unrealistic, and the prime cause of public- private conflict.

There are marked differences over which government assets and services should be retained. The global experience on the matter can be a guide for the way forward. Countries such as Singapore supports the interplay of competitive market forces and the government. In Bhutan, government enterprises function in an environment where the incomes of beneficiaries are so low that the supply of services can be provided only with a subsidy. resistance to privatizing represents an aversion to transferring assets and services to society members who would be enriched by the transfer. These differences emphasize the need for extensive public awareness programs for leaders, constituents, government agencies, and PSE staff on the benefits of privatization.

Tacit agreement for privatization often goes with a lack of commitment within government. This situation arises from misconceptions of the consequences of selling too cheaply, without adequate rehabilitation, without retaining a vested interest, without regulatory controls, and without appropriate due diligence.7 Prominent staff often defend the capacity of management to operate PSEs efficiently and are not interested in the wider benefits of privatization. These factors point to the need for vesting decision-making powers in an autonomous institution and ensuring that privatisation.

Support our journalism by subscribing to Taxscan premium. Follow us on Telegram for quick updates